Dorothy Louisa May was born on 21st July 1922 in South West London. Robert Ambrose May and his wife Frances Honoria already had two children, Gwendoline (Gwen) and Bernard and would have a further son, Joseph, when Dorothy was three years old.

It was Bernard that Dorothy was closest to in age, however, and there remained a strong relationship between them as siblings throughout their lives together. It is no accident that surviving photos from this time specifically picture these two children playing together.

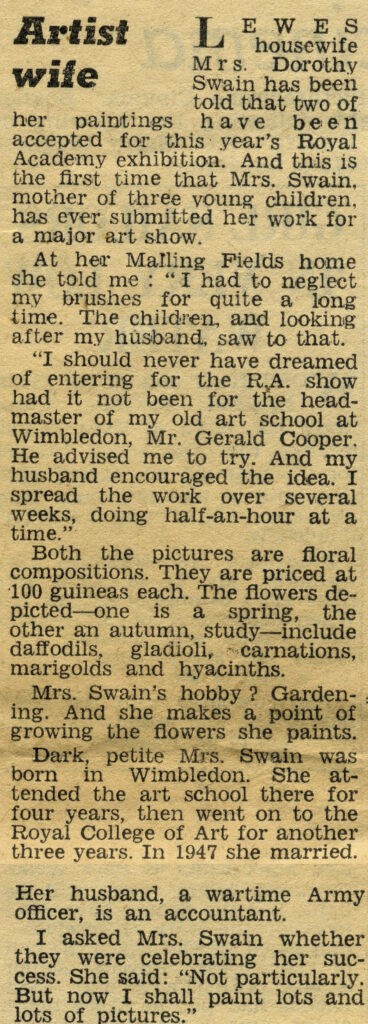

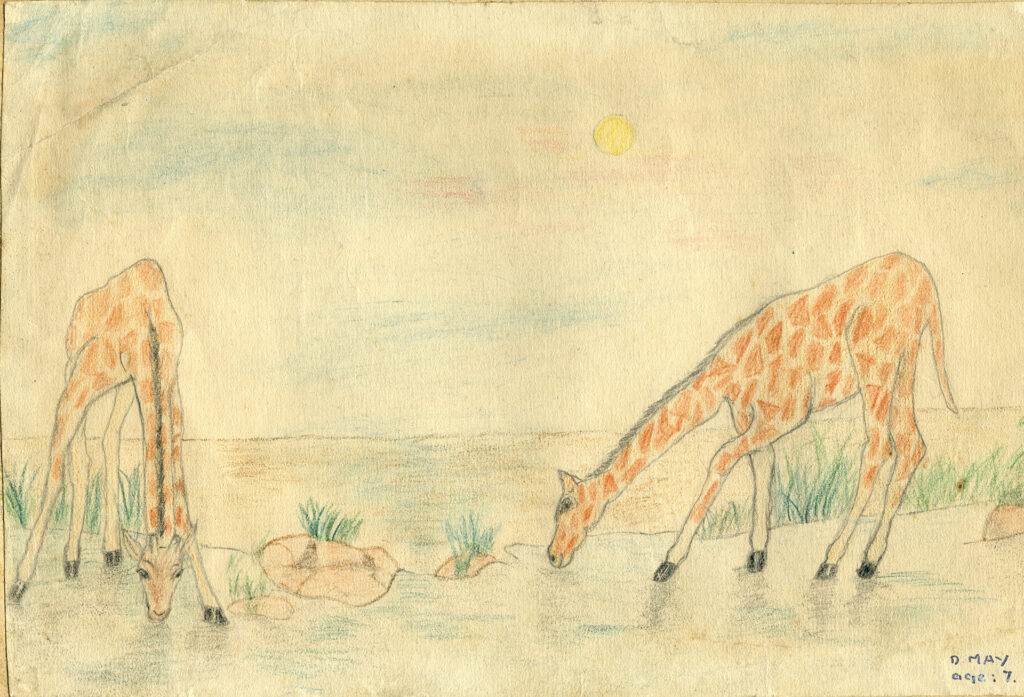

Her artistic flair was evident from an early age as shown in this drawing of giraffes that she completed when just seven years old.

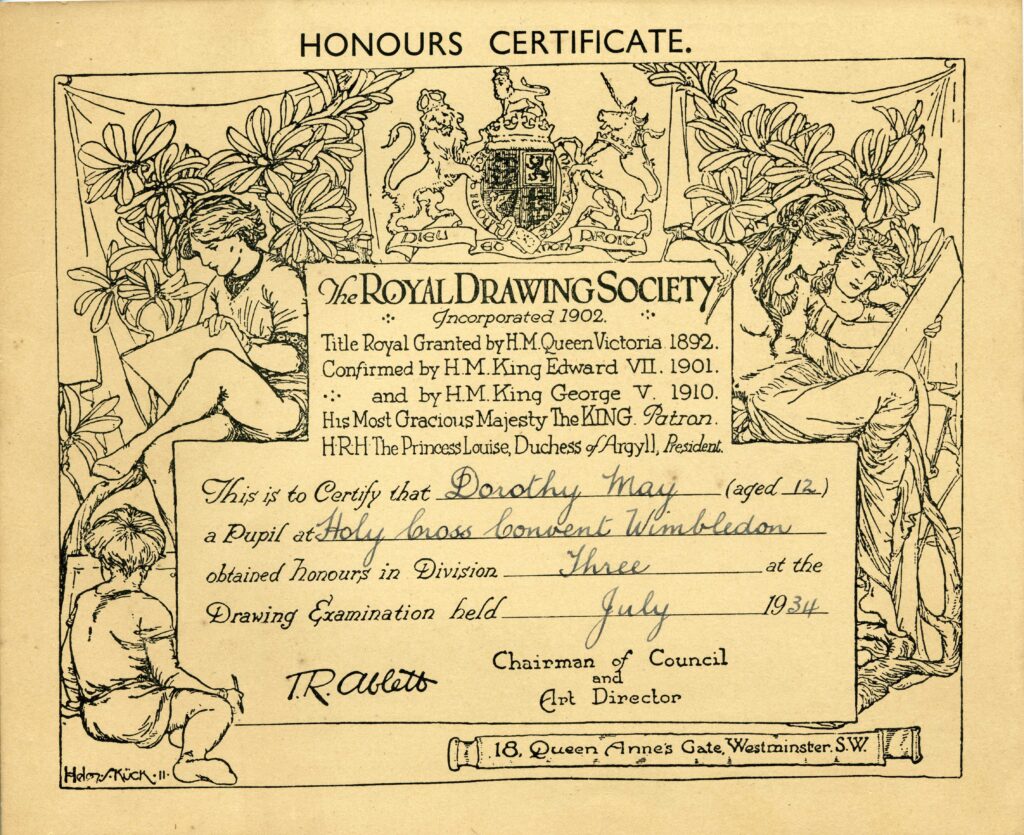

Dorothy was educated at the Holy Cross Convent in Wimbledon, where she pursued eight subjects to Junior Local Certificate level, these being English, Geography, Religious Knowledge, Latin, French, Arithmetic, Mathematics and, of course, Art.

Four years later, her attentions and drawing subject matter had turned to a creature much closer to home, her own pet toad, Tom. In between stroking his head and hunting insects in the garden to feed him, Dorothy produced a fine sketch.

A year later, at the age of just twelve, she was entering work into the Royal Drawing Society examination, which she passed with honours.

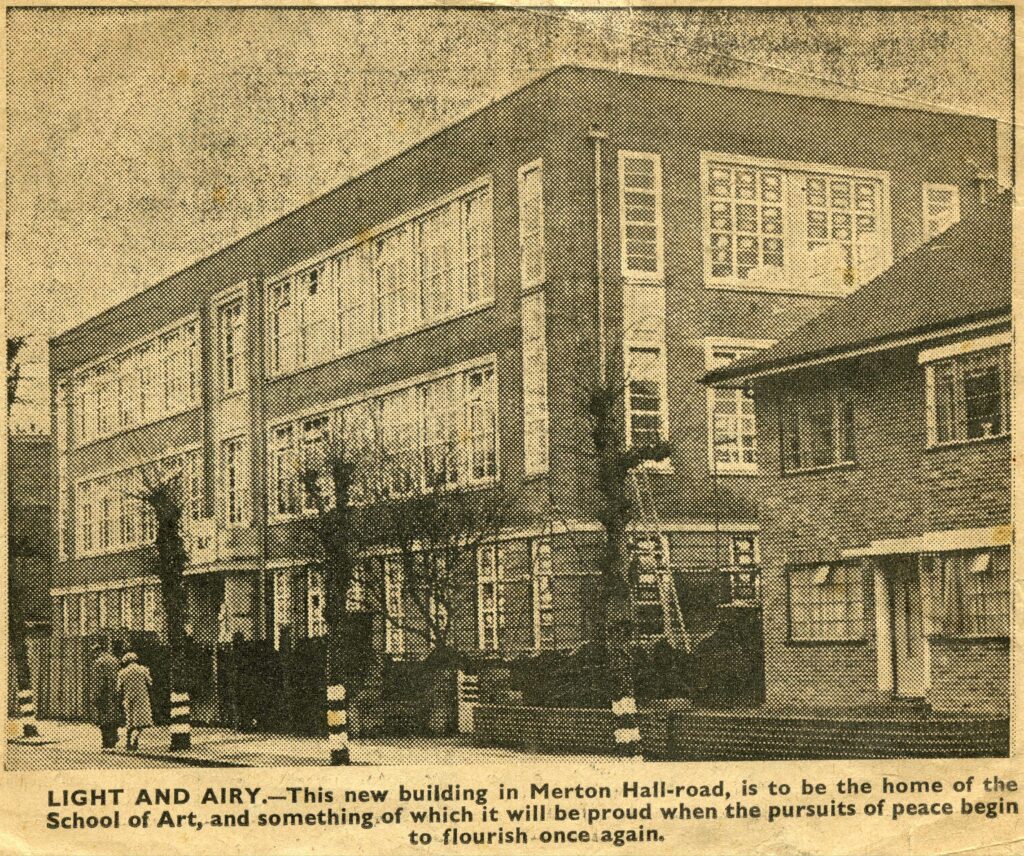

The May family were by now living in Cromwell Road, Wimbledon. This house had space enough to permit the development of a studio room, which Dorothy made extensive use of alongside her sister, Gwen. The location of the family home also allowed her to further her artistic development by attending the nearby Wimbledon School of Art (now Wimbledon College of Art), when leaving school in 1938.

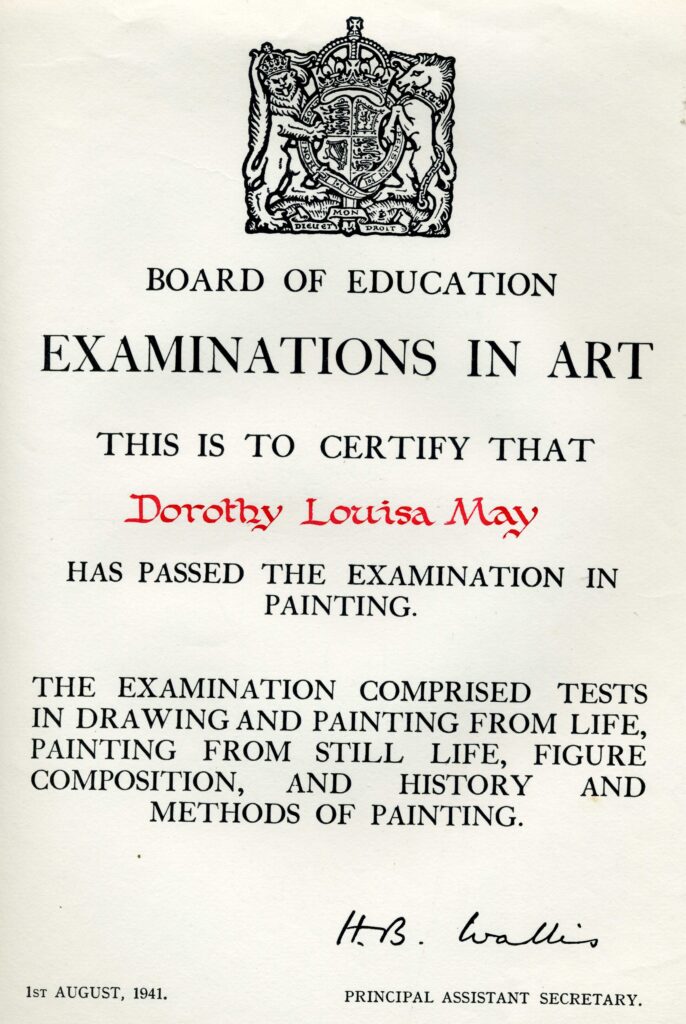

At Wimbledon she received teaching from such names as Robert Buhler, who helped introduce modernism, which reshaped the British portraiture tradition, and Lionel Ellis, the wood engraver, illustrator and artist, together with Robert Baker and James Hockey, later principals of Burslem Art School, Stoke-in-Trent and Farnham School of Art in Surrey, respectively. Under this collective of excellent tutelage, Dorothy passed both the Board of Education Drawing and Painting Group Examinations necessary to enable her to teach art.

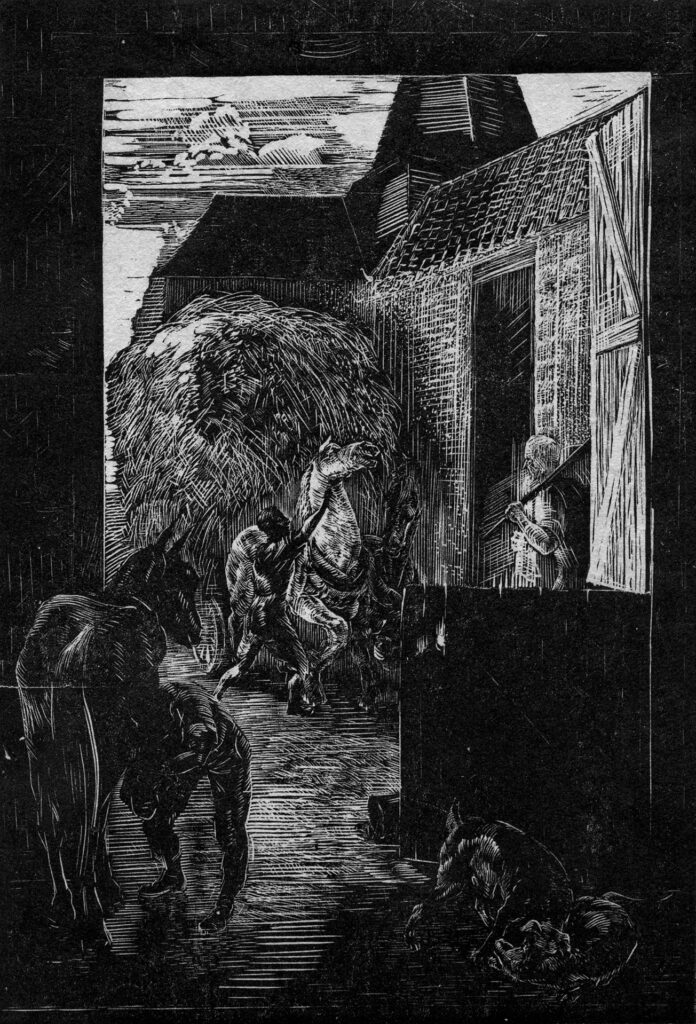

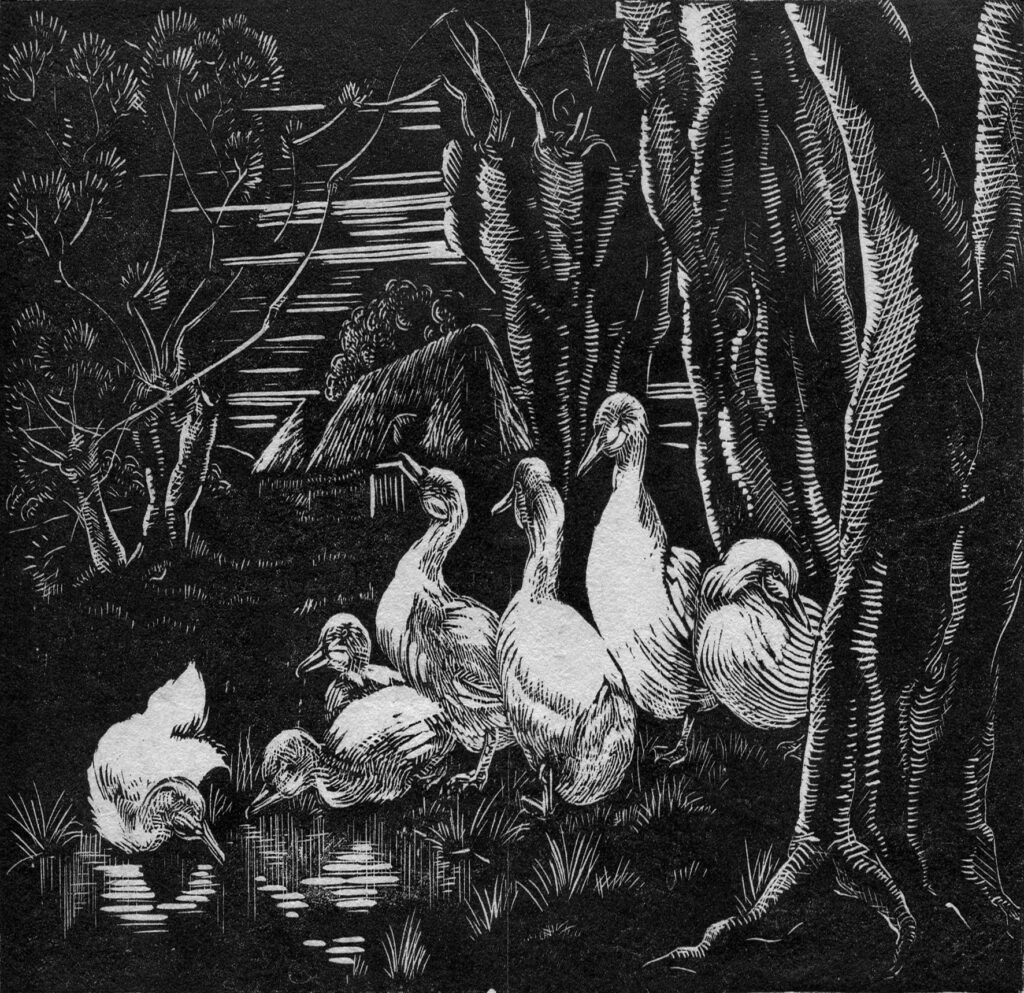

Wimbledon School of Art was to prove an opportunity to develop her own technique, with her teachers developing a fond respect for Dorothy’s work across the artistic disciplines, including the development of exiguous woodcut blocks for use in printing.

Writing in June 1947, James Hockey stated, “I remember your wood engraving at Wimbledon well and am glad to hear that you propose to continue with it”, but was unable to help with Dorothy’s request for tools and equipment.

Likewise, after noting his pleasure to learn that Dorothy was happily married, Robert Baker, writing to her in the same year, seems to have been responding to Dorothy’s request for information on suppliers of clay and for kiln building designs in order to produce “church terra cottas and clay figures”. No clay figures nor a record of Dorothy’s post-college woodcut engravings remain and it may well be the case that difficulties in obtaining the materials and the financial constraints often associated with young couples, only recently married, prevented their development.

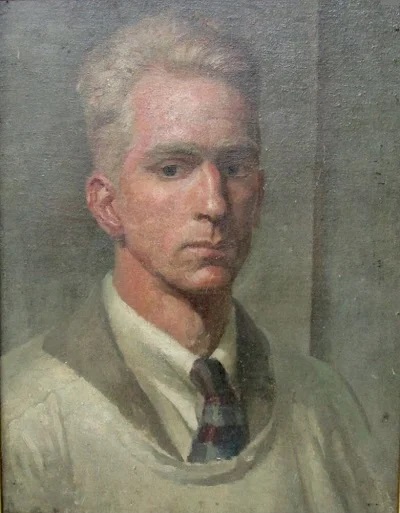

What was engraving and pottery’s loss, was to prove oil painting’s gain, for here was another field in which Dorothy had excelled. Since becoming independent in 1930, the Wimbledon School of Art had run under the headship of the famed flower painter Gerald Cooper, with whom Dorothy continued to correspond on-and-off for many years. This exchange of letters not only suggests that Cooper had succeeded in making a lasting impression on Dorothy, but that the admiration was not simply one-way.

Indeed, in one letter, believed to be from 1949, Cooper states, “your work has a charm of a personal quality which is worth while”. Later, after bemoaning his busy work schedule as a painter, he concluded his letter, “I often think longingly of you as a possible assistant. I know no one who paints flowers with the verve, charm and beauty of colour which you manage at your best”; quite a statement from an artist of his calibre. His respect is confirmed in a letter dated January 1974, when after a break in contact of what seems to be around twenty years, Dorothy was told by return “I remember you very well and your painting too”.

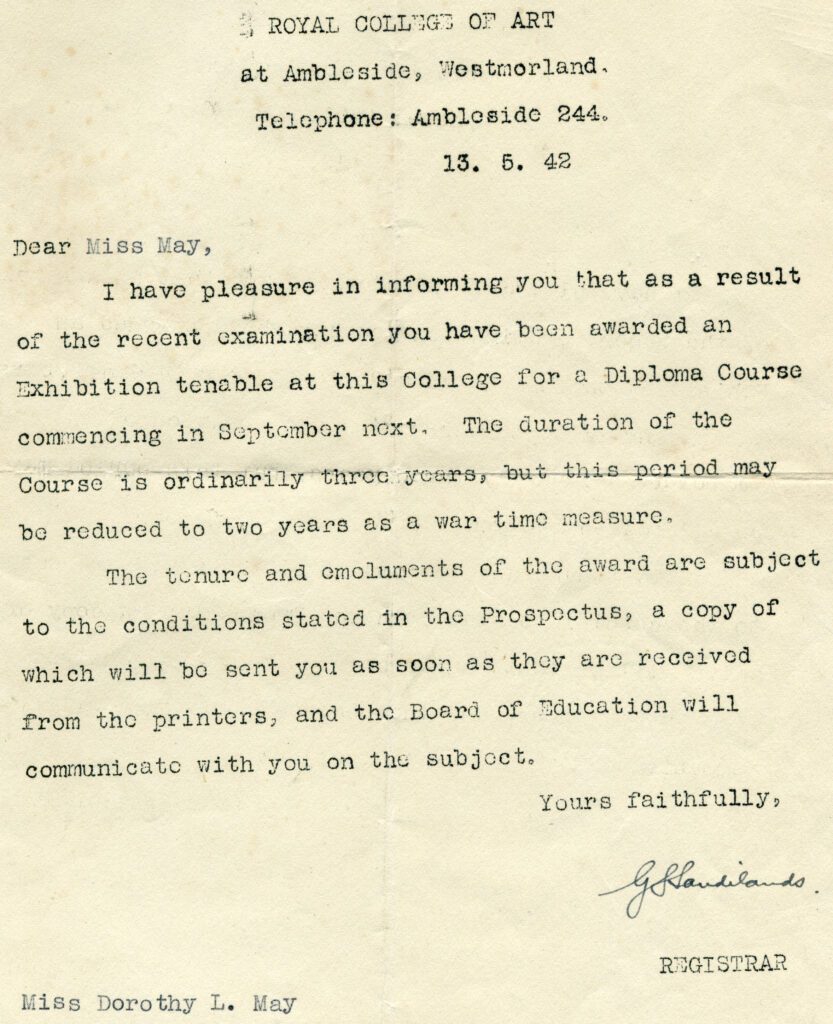

With such critical acclaim for her painting, it may be of little surprise that Dorothy’s ability saw her pass the 1942 entrance exam for the Royal College of Art. With the interruptions of the Second World War, however, this was not an option she was able to pursue until later.

Relocation was to be one of the themes of Dorothy’s life during the war years, with even the Wimbledon School of Art moving whilst she was a student, into its current premises in Merton Hall Road, which a local newspaper described as both “light and airy”.

From Wimbledon, she then briefly taught art as an unqualified student-teacher at the nearby Holy Family Convent in Tooting on a part-time basis for eight shillings an hour.

She combined this with work as a tutor for Hillcroft College, which offered a correspondence course in painting for army personnel. This latter position she took over from the illustrator W. G. D. Hill and was a heavy commitment at first, since Hill’s other commitments meant he had somewhat neglected his role as tutor for some time. He wrote to Dorothy to apologise and to say that once this backlog had been dealt with, “you will find the weekly correspondence amounts to between 6 to 10 letters and can be easily dealt with”.

These positions occupied her until joining the Women’s Farm and Gardens Association as a land girl in 1943. This new work took her first to Lacock, the picturesque Wiltshire village that was home to the development of photography. The new environment would take some getting used to, as indicated in a letter from her father dated 3rd March 1943, soon after having started the work, “I am rather shocked at your conduct in walking into the major’s bedroom and can quite understand his temporary embarrassment. I expect you will never hear the end of it”. The amusement continued on one stormy night, when Dorothy was sent out to comfort a goat, which proceeded to devour each of the buttons on her dressing gown!

The new work required time to get to grips with. In the same letter, her father wrote, “I hope you have a suitably light spade to manipulate. You must not overwork yourself though by trying to do too much before you are fully hardened off”. Owing to the physical nature of the land work, Dorothy often found that her appetite exceeded the portions of food allotted to her. On one occasion she wrote home to say that she had been so hungry that she had eaten an entire jar of fish paste and, as a consequence, a home-baked cake was sent without delay.

It was not all hard work though, with time for some relaxation. Lois Cornford, who later became a student of Dorothy’s mentioned in her recollections of painting classes with her that “she told us all about her time when she was digging for England and more besides! Hard work and great times she told us!”

These great times included playing table tennis. It was over this net that she first became acquainted with a junior army officer who was stationed nearby, one Alfred Charles Swain. While marriage was still four years off and the war would keep them apart for long periods with Alfred part of the Middle East forces, the relationship was soon a serious one, as evident by the fact that Alfred began to correspond with Robert, Dorothy’s father.

Despite the benefits of being in Lacock, the distance to Wimbledon and the anxiety brought about by being separated whilst at war, understandably seems have to been a strain upon Dorothy and her family. On the 10th August 1944, just a few weeks before he passed away, Robert May, writing in reply to a letter from Alfred, mentioned that, with Dorothy’s relocation to nearby Chalfont, “we see her at weekends, which is much better alround (sic.) than when she was at Lacock. She seems a lot more interested in her work too even though it is hard going some times”.

Along with relocation, sadly the war brought with it another theme; one of personal loss. Her much-loved brother, Bernard, died in 1943, tragically being shot down over Algiers just fifteen days after her father had written to Dorothy, in a letter dated 6th June, to say that her brother had returned to his squadron after leave to “finish off his few hours left to complete his two hundred and consequently free himself from any more dangerous work for some time”.

What is more, Dorothy lost her own father one year later. He seems to have suffered heart problems, perhaps due to overwork since, writing in 1942, he commented that his work “entails attendance on the seven days of the week and is necessitated by the adverse effects of war-time conditions on financial journalism” in the editorial offices of the Financial Times and the Sunday Times.

Dorothy was now not just driven by passion for art, but by a real and pressing need to qualify fully as an art teacher and be able to support a family that had been robbed of its two principle wage earners. Her own application for a study grant, signed on the 5th February 1945, tells its own story; “I have lost my father and elder brother during the war and have no income, nor any means of obtaining assistance from my family, and unless some allowance can be made I shall not now be able to complete my studies for the teaching profession”.

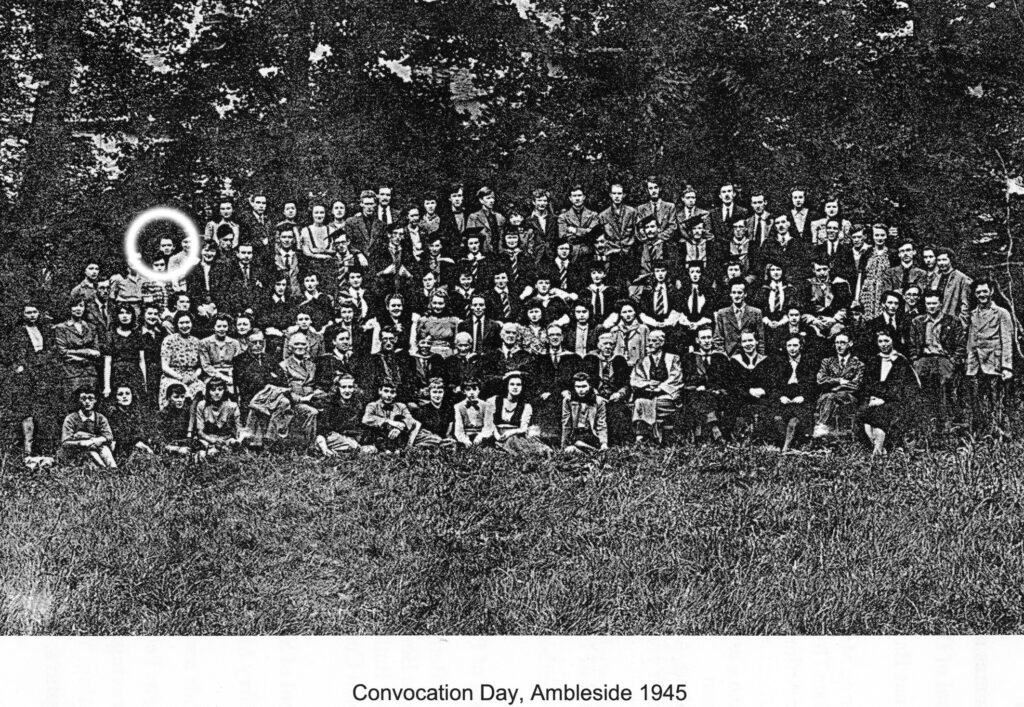

With this double helping of loss and grief, she was discharged from service on compassionate grounds and, in January 1945, finally had the opportunity to pursue her love of painting at the Royal College of Art.

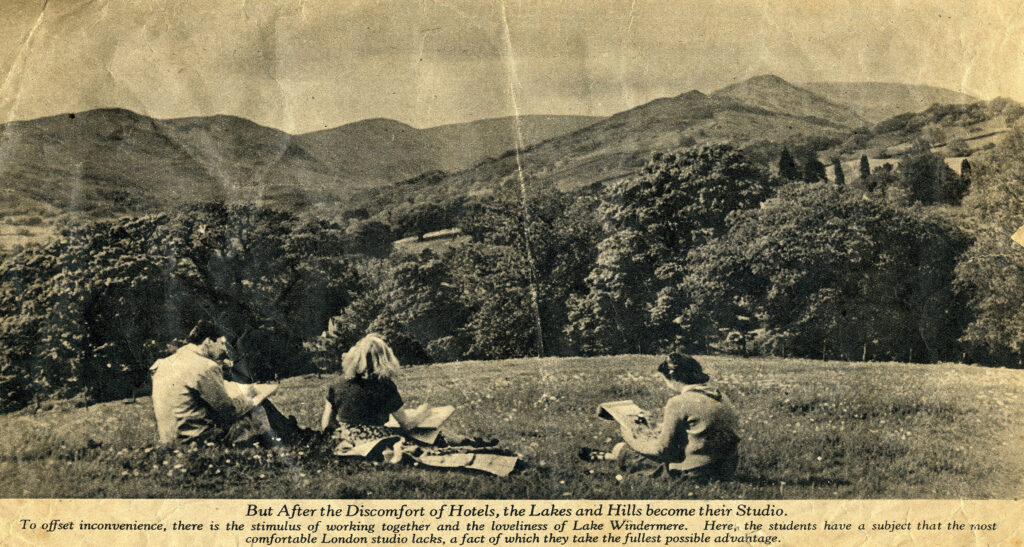

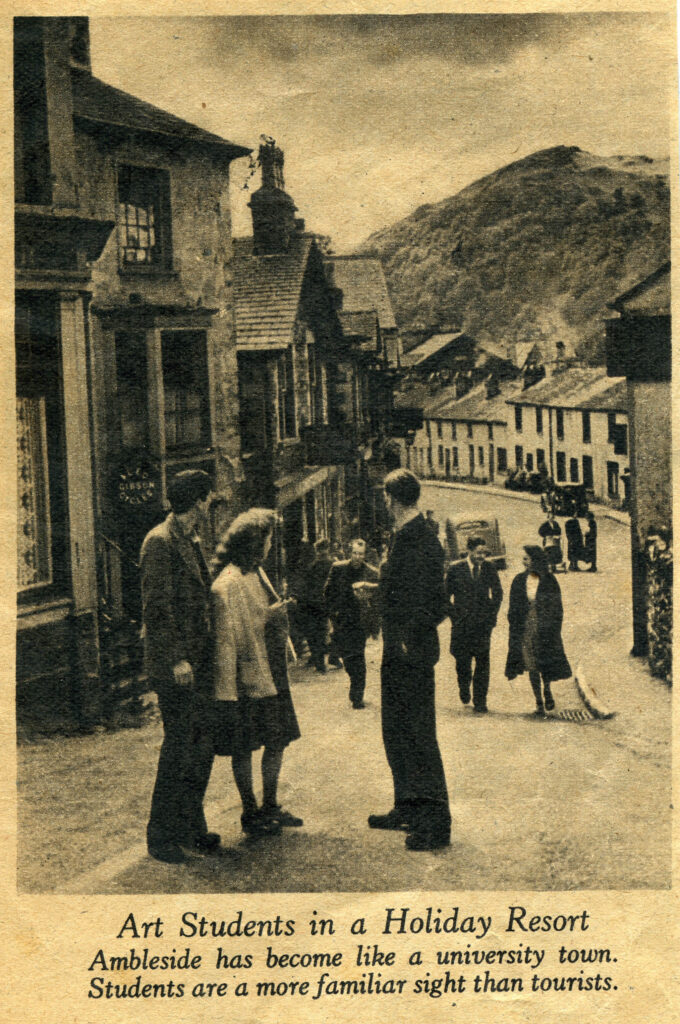

The College had by now temporarily relocated to Ambleside in the Lake District to avoid the German bombs falling on London. The students were housed in guest accommodation and for all of her time there, Dorothy was housed in the Queen’s Hotel, in the very centre of the town. A local newspaper reporting the sudden and unusual influx of students to the area commented that at least having the surrounding lakes and hills for a studio would make up for “the discomfort of hotels” and their temporary nature.

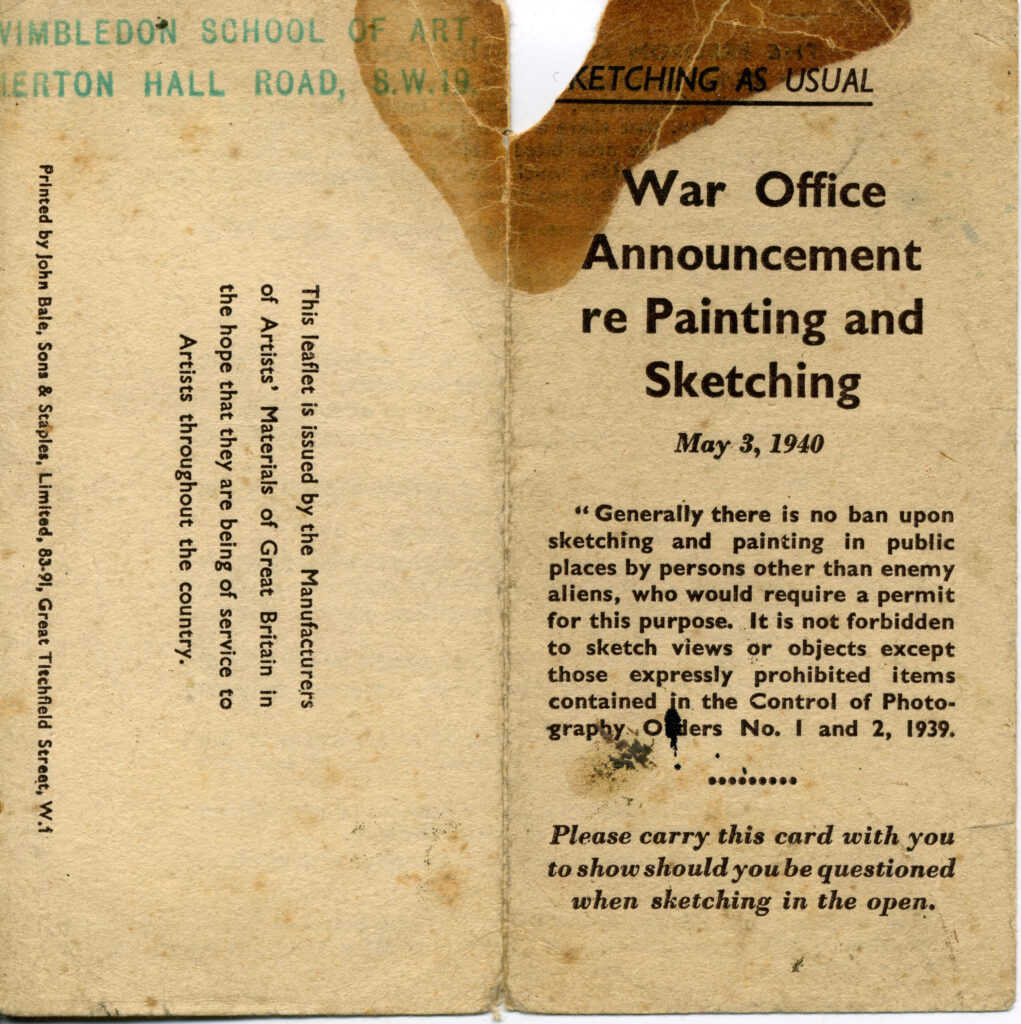

Wartime disrupted the art profession in many ways. As an art student, Dorothy possessed a card printed for British artists, entitled Sketching As Usual : War Office Announcement re Painting and Sketching. It was recommended that this card be carried at all times “to show should you be questioned when sketching in the open” since it highlighted a law passed on 3rd May 1940 that “generally there is no ban upon sketching and painting in public places… It is not forbidden to sketch views or objects expect those expressly prohibited items”, which included defences, fortifications and infrastructure.

The recent loss of her dearly beloved brother and father meant that even the obvious attractions of being an artist in the picturesque Lake District did not prevent Dorothy from unhappiness as she stayed far away from what remained of her family. She has often remarked that her time as a Royal College student was one of the most difficult periods of her life.

Following the end of the war, life began to take an upwards swing. In early 1947, on January 11th, she was married to Captain Alfred C. Swain with a reception held at the Wimbledon Hill Hotel (now the Dog and Fox public house).

Family life began very soon after marriage, with her eldest son, Francis, born in November, even before the happy couple had celebrated their first wedding anniversary. No doubt this brought with it the need for yet more adaptation, but Dorothy seems to have been no stranger to this. Gerald Cooper writing to her in 1949 commented that “I am accustomed to your lightening changes of appearance, which would, you must admit, have bewildered a common man…. (but) I expect your present role of materfamilias suits your personality better than any of the previous adventures”.

This new materfamilias was starting out her adventure into married life and motherhood in the small village of Newton Poppleford, in South Devon. It was here that Dorothy soon discovered that she would be having a second child. This may have precipitated their subsequent relocation, though this may equally have been as a consequence of Alfred changing jobs.

The family moved to Sussex, which was to become Dorothy’s stamping ground for the next nearly sixty years. They moved briefly to Hayward’s Heath where her second son, Christopher and her first daughter, Teresa, were born. Soon afterwards, they settled at Woodbine Cottage in the Malling Fields region of Lewes. Dorothy was very happy at Woodbine Cottage and she and Alfred did a lot of work on the house and garden together.

Despite the more suitable surroundings and her efforts to obtain materials noted above, the pressures of young family life with three small children seem to have prevented Dorothy from dedicating herself to her art as much as she would have liked. The discipline required is evident in a note Dorothy wrote to herself to have “Painting Daily Practise 9:30-10:30 (pm)”. She tasked herself to “each day complete one (board) with a quickly executed study to capture a specific joy. For one hour aim at realism, truth and joy”.

This hour was not the limit to her concentration on art, however, since she also aimed for half an hour’s work from 3pm on any one of her incomplete paintings and, moreover, recognised the need to “get into habit of collecting material (actual, imagination or remembered) throughout the day and note it down so that no time is lost at 9:30 in choosing subject matter. Note by sketching also”. The subject matter in question was limited to her own six suggestions:

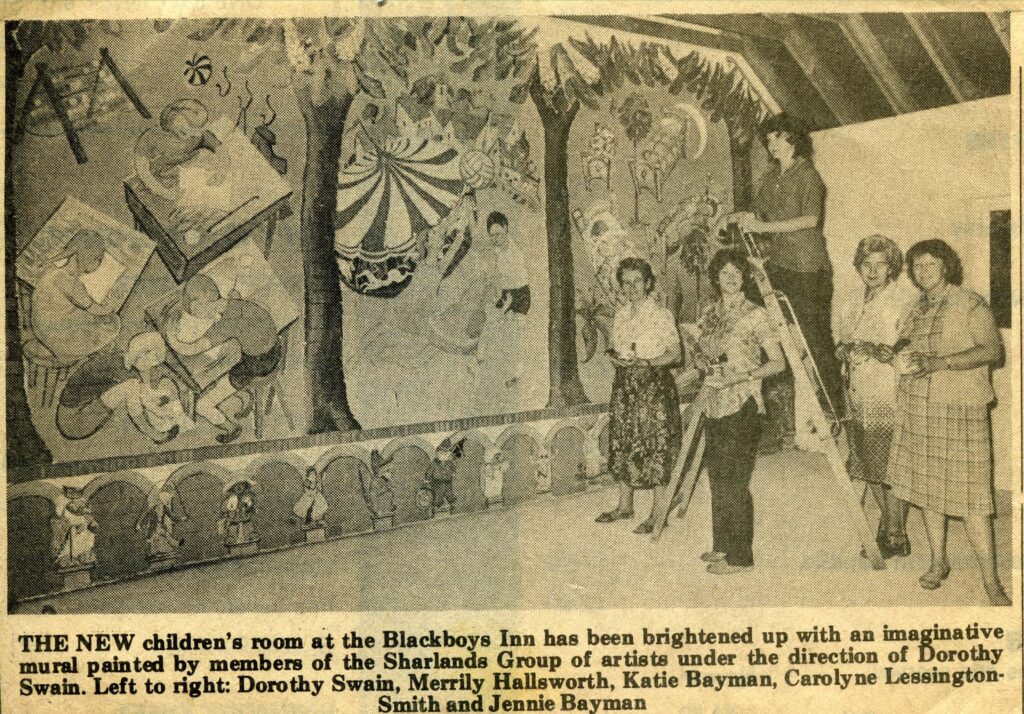

It was not, however, just the group of painters that was affected by these classes. Dorothy’s investment of time and energy did not stop with those immediately around her. Together with her painting group, she was a vital part of a team that undertook to decorate one wall of a children’s room at a local public house, the Blackboy’s Inn, with a mural. A local newspaper article from the time records that Dorothy designed and directed the work and completed a large part of the mural herself, which took a total of two months to complete. Again, with a gentle humour, Dorothy was reported as saying “I have done mural work only a couple of times before. I enjoyed doing this one and I just hope the children do not take it upon themselves to add impromptu contributions to the painting”!

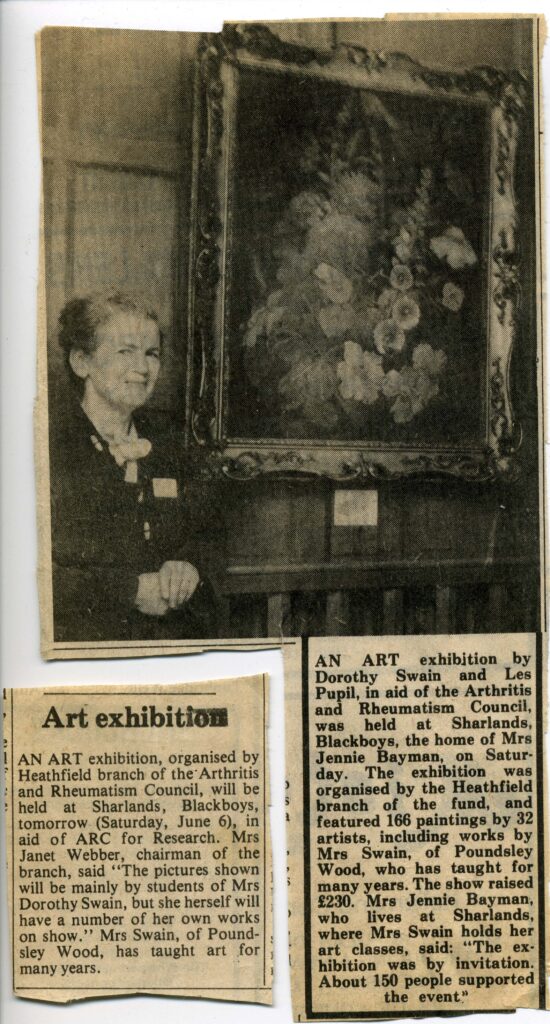

Her painting group was also involved in charity initiatives. One of the students, Janet Webber, was chairwoman of the local branch of the Arthritis and Rheumatism Council and the group put on an exhibition of their work, which included Dorothy’s, at the house of another student, Jennie Bayman, where Dorothy also taught classes twice a week. In total there were 166 paintings by 32 different students. This again made the local news, where it was reported that £230 was raised for the charity through the event.

Dorothy, on her own, was also involved in at least one further charity initiative, this time in support of Action Research for the Crippled Child. At nearby Possingworth Manor, a Jacobean house of some note, she was invited to exhibit paintings for sale on the understanding that twenty percent of sales were passed to the charity. As it happens, she sold one painting for £500 and so passed over £100, for which she was thanked for her generous contribution to the charity.

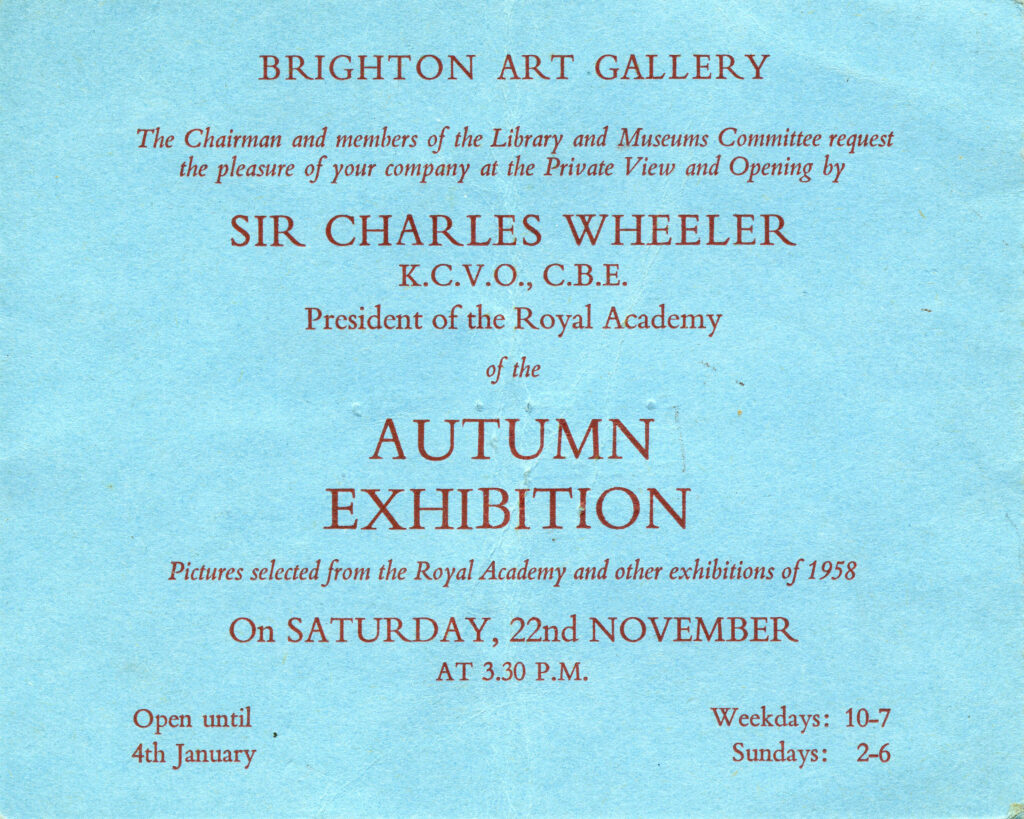

At this time, Dorothy’s works were also permanently on exhibition and on sale at the Premier Gallery in Eastbourne, owned and run by a dear family friend and another of Dorothy’s students, Dino Mazzoli. When approached for recollections during the preliminary stages of researching this current book, Dino Mazzoli helpfully included a number of newspaper articles and photographs from his own private collection. Despite being on the verge of an operation to correct his sight and being somewhat housebound, he also wrote over a dozen pages of very touching memories which, for the sake of brevity, cannot be reproduced in full, but are well worth referencing.

Before knowing Dorothy, Dino Mazzoli worked as a tour guide visiting some of Europe’s finest art galleries, the Louvre, the Prado and the Uffizi to name but three. A series of coincidences brought him in touch with the wider family, but it was not until 1980 that he was walking along the High Street of nearby Heathfield and noticed a sign for an art exhibition at the local Red Cross Hall. A still life painting was standing at the entrance on an easel and, despite having seen the Masters across Europe, seeing this work was what Dino Mazzoli described as a “pleasant shock”. He continued his narrative, “now, all at once, in a street of an English village, at the entrance of a small room, I was facing with a work which had all the numbers of a masterpiece: Still Life with Tea-Pot, oil on canvas, signed D. Swain”. This impression was magnified considerably when visiting Dorothy at Woodbine and seeing her paintings everywhere. He records that “the first thing that went through my mind was the most logical at the time ‘how can be that such a great artist is practically unknown’?”

From his writing, it is clear that he thoroughly appreciated not just the art and the artist herself (as well as her family, which he described as being the number one, aside from his own, that he had encountered during 51 years in England), but also the manner in which Dorothy taught, which was by taking a mentoring approach. He recounts, “when she come around (her class) to see how work progressing, she just stood and look… then she used to say, always with the ‘Dorothy’s calm’ those few words that opened my eyes to what the painting needed – she knew always and immediately how to change a confused mixture of line, colours into something that could express better my way of saying something without taking brush and: ‘do this, do that’”. She used her experience and perception to empower her students and help them to properly see.

The Woodbine classes continued until 1987, when Dorothy and Alfred moved to “Hawthorn” on East Street in Mayfield. It was also here that Dorothy finally gave up her painting classes in 2003, much to the dismay of her students. It was also where her husband of almost 48 years sadly passed away. Alfred had always staunchly supported her art and had regularly driven her out to painting spots in the depths of winter before heading off in search of a cup of tea for her already chilled hands. Daughter Veronica recalled that “when they’d been away, maybe to Devon for a few days, he used to proudly say when they came back something like ‘we knocked out six paintings last week’ – I used to particularly like the way he said ‘we’!” He also supported his wife and her painting groups by sorting out suppliers and placing orders for materials, an area in which he excelled. His loss must have been keenly felt.

Dorothy’s health also took a knock when living in Mayfield, with heart problems at the age of 84 prompting an operation to insert a stent. The pace of life needed to change and Dorothy had to turn her back on her regular custom of waking in the middle of the night and taking herself, her palette, her easel, her canvases, her paints and her brushes down country lanes and along footpaths to set up and be all prepared to capture the magical mood and colours as dawn broke.

She did, however, continue to enjoy any opportunity to undertake trips with her family on which she could paint. In 2006, one such trip took to her to Giverny in France, where she was able to complete several paintings in the scenic surroundings of Monet’s famous house and gardens, whilst also enjoying a visit to Les Tuilleries to see the great artist’s triptychs of water lilies. A year later, she had at long last the opportunity to visit the Yorkshire Dales, the area of England she had most wanted to visit and had never been able. Here, she completed a canvas a day.

In 2011, with her health sadly further compromised, she returned to her old stamping ground by moving into the Nursing Unit at Holy Cross Priory at Possingworth Place near Cross-in-Hand, just two miles from the second Woodbine Cottage, where she was at her most prolific. Even there, until within a couple of years of her death, she continued more often than not to be found with brush in hand. She passed away 31st January 2018 at the age of 95 and is much missed by family and friends.

It was between these two trips that her children decided that Dorothy should move into an urban setting, in this case the Kentish town of Tonbridge, in order to be closer to family and be within easy walking distance of shops and a doctors’ surgery. In her new surroundings of Eastfield Gardens, she continued to paint, but remained physically less active than before and turned more and more of her attention to finishing or reworking canvases from the past.

1. Actual person, plant or light falling in house

2. Study of something in or from garden

3. The weather and its moods

4. From vivid memory of the past

5. Illustration from Bible, poetry or descriptive prose

6. Copying from a masterwork