There is a world of difference between portraiture and photography. The skill of figure painting is not to show off technique and cleverness in trying to capture a true physical likeness. Such a pursuit would render portrait painting dull and remove much of the very creativity there exists in art. In Dorothy’s own instructional booklet on figure drawing, she insists that a basic understanding of physical anatomy is essential to be able to depict the human form with understanding. It is, for example, impossible to detail where there is flexibility or rigidity, weakness or strength unless there is a “a firm grasp of how the main muscles of the body work in conjunction with those which give counter-action, as only then are we ready to ‘understand with a pencil’ what we see”.

Yet, knowledge of the physical is not enough, since portraiture demands an understanding of what makes a person tick; who they are in their innermost being. Yet, this is still not enough, since portraiture should go beyond what a person looks like and how they work into why they work, looking at the spiritual force behind life itself. Portraiture should, as it were, glimpse a person’s soul as perceived by the artist. With this in mind, Dorothy made a note of a quote from an unidentified source, “the body, the hands, the face, each reveals the inner spiritual state of the personality. To the man who knows how to read these signs they offer a visible portrait of the man within”. Her role is to portray not what is seen but what is perceived, “which may necessitate exaggeration, distortion, definitely simplification, but above all a thorough knowledge of what goes on in the human form”. For this reason, Dorothy’s recommendation was literally to take careful note of the first impression, the preciousness of which can often be lost in the labour of execution if a few words are not penned at the outset to give the artist a tangible reference, if required.

The portrait should, however, not merely reflect the subject, but be mingled with the artist herself, her personality and her feelings, harnessing “the rapport of human emotions and the interplay of human movement to express a much wider field of experience”. To this end, Dorothy commented that “good painting comes from an ecstasy of joy or the height or depth of any other emotion”. A portrait artist should also draw upon her ideas and her experiences, drawing on the past even as far back as childhood, since “personal comment from our own life’s experiences will be what is of value at the end”. In this way, what Dorothy called “a message of deep thought” will be portrayed on the canvas, not merely the subject. This is what distinguishes a truly great portrait and it matters not what medium is used to make the depiction, be it oil paint, pencil or any other, since “it is the mind that paints not the medium. The principle is the same for all”.

Once the figure has been thought onto the canvas, where it is positioned needs to be carefully considered. The subject for the portrait should be placed in the most telling part of the canvas, so that the rest of the composition harmonises around it like a symphony. It is then important to ensure that the figure’s balance is noted for where the weight is pushed up by the ground beneath. A figure must be so rooted in order to lend the composition a sense of stability. With the basic figure in balance, the rest of the composition can be built. During this phase the temptation will be to focus in on specific parts, but the artist must always think of the whole composition to avoid parts of it getting quickly out of balance. This applies to line and rhythm, to tone and colour, to all components of the portrait. As for the quality of these lines, Dorothy reminded us that “of all things living, curves are strong, vigorous and never sweetly arcs of circles. It is this virility of curved line which differentiates living things from the lifeless”.

Portraiture

Figure Drawing

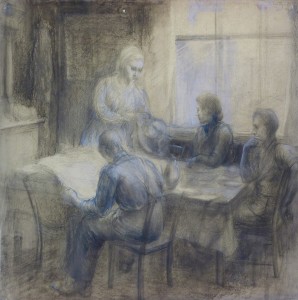

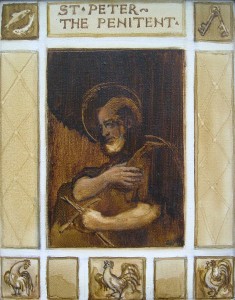

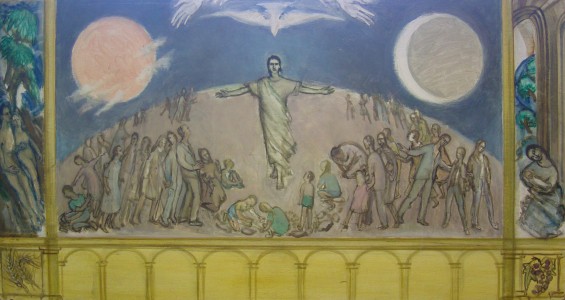

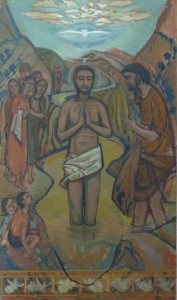

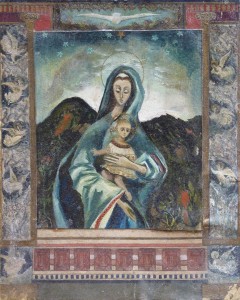

Religious Art